Taking Thought Experiments Seriously

What thought experiments really mean, and how not to engage with them.

[Although this post is about philosophy, I’ve written it with a layperson audience in mind. So I’ve omitted some nuance for the sake of simplicity and clarity. I hope this isn’t too offensive to my philosophy-minded readers!]

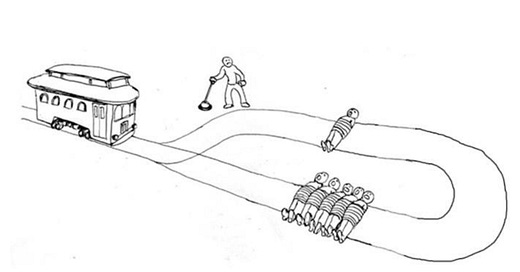

Philosophers often like using thought experiments, a kind of imaginary scenario that they’re using to illustrate a point they’re making. Some thought experiments have become rather famous - most people are familiar with the trolley problem or the Ship of Theseus. Those of you who’ve dabbled in AI discourse might also have heard of the Chinese Room thought experiment. Despite their increasing popularity, I think thought experiments remain very badly misunderstood1. So I wrote this post to try and clarify what they are, what their point is, what other kinds of imaginary scenario you ought not to confuse with them, and some common mistakes people make when engaging with them.

How Thought Experiments Work

We all have intuitions about philosophical subjects. For example, you probably have intuitions about how time works, or whether murder is wrong (or, perhaps, whether anything can be wrong), or what it means to know something. Philosophers care a lot about these intuitions. Saul Kripke, one of the most famous and important philosophers in the world, wrote in Naming and Necessity that he thought an idea having intuitive content was the most conclusive evidence you could have for it!2 Now, not everyone agrees with Kripke. For instance, Lance Bush thinks that certain kinds of philosophical intuitions don’t actually exist. But let’s set the questions of how important intuitions actually are aside for the moment. It’s a brute fact that philosophers think they are, and so they have devised thought experiments as a way of getting at them. Most people agree that thought experiments are really useful; even Lance uses them.

But why do we need thought experiments to extract our intuitions? Well, we wouldn’t, if all our intuitions were printed out in a neat list for us to peruse at leisure. But we aren’t so lucky. Our intuitions tend to be muddled, contradictory, uncertain, and sometimes unconscious. Some are held so deeply that they don’t feel like intuitions at all and instead appear as obvious truths. So we need thought experiments to drill deep into our mind and extract them in useable form, similar to an oil rig. Like actual oil rigs, some thought experiments will also try to refine those intuitions, carving away all the contradictions and reshaping them from inchoate vibes into sharp and precise ideas. As you might expect, this helps immensely when we’re trying to get clear on complicated concepts.

This is the reason why thought experiments are presented as imaginary scenarios. You might never witness a murder in your life, but you can still draw out the intuitions you have about murder by thinking about how you’d respond to a hypothetical one. This also allows philosophers to posit things that don’t exist, like time machines, to draw out your intuitions about time! The imaginary nature of thought experiments gives philosophers a ton of freedom in constructing them just right to get at the intuition they want, as well as the ability to adjust details of necessary.

There are a few things philosophers can do with thought experiments.

They can use it to shed more light on your views. For example, lots of people don’t have a fully worked out moral philosophy. But if someone eg. refuses to pull the lever in the trolley problem because they think it’s too heartless to intentionally kill someone, even for the “greater good”, then tells us a lot about their moral intuitions. They can then use that insight to flesh out their morality a little more - perhaps this makes them realize that they’re attracted to Kantianism, which says you must never use a person as a means to an end.

They can use it to categorize people and philosophical views. In Mary the Color-Scientist, people are divided over whether Mary really learns something new when she steps out of the colorless room. Very crudely speaking, the people that say no have physicalist intuitions, while the people who say yes have anti-physicalist intuitions. Seeing this split allows philosophers to draw out battle lines in debates about how the mind works - and hearing how people justify their intuitions may suggest further subcategories of views3, or perhaps hint at arguments they might make.

They can try to convince you to agree with them by showing that deep down, you already do! Daniel Dennett calls this an intuition pump. In cases like this, the thought experiment functions like an analogy. If you have intuition X in the thought experiment, and the thought experiment is analogous to some situation they’re arguing about, then you ought to also have intuition X in their situation - which is the one that supports their view, of course. Such philosophers have to make sure they don’t accidentally change details which make the experiment disanalogous from the case. Sometimes much of the debate about an issue is just arguing over whether an important thought experiment is analogous or not.

Thought experiments can make difficult ideas clearer. Later on in Naming and Necessity, Kripke tries to explain the difference between a proper name and a description, which turns out to be surprisingly complicated. To help make things clearer, he uses a thought experiment where Kurt Gödel plagiarizes the research of a man named Schmidt.4 By turning abstract ideas into a concrete scenario, he helps his audience visualize and understand the difference much more easily.

In some abstract areas of philosophy, thought experiments can prove things by themselves. For example, some philosophical debates are about whether a certain thing is logically possible. If you can cook up a thought experiment that shows how it might happen, you’ve proved pretty well that it’s logically possible! This is a rare way of using thought experiments that doesn’t involve intuition - although I suppose you could say that it draws out the intuition that the thing is logically possible?

I’m sure there are uses of thought experiments that I haven’t covered here. But these are the main uses that you’ll probably run into, especially if you’re a non-philosopher and won’t encounter the really esoteric ones.

Mistakes about Thought Experiments

I hope I’ve at least convinced you that thought experiments have real use, and aren’t just a silly toy. And if that’s so, then you ought to take them seriously and try to engage with them on their merits and respect their uses. Unfortunately, a lot of non-philosophers frequently make mistakes in their engagement with thought experiments. Let me explain what those mistakes are, so you can avoid them.

Complaining about Unrealistic Experiments

“The trolley problem doesn’t make sense. How can someone tie six people to the tracks without getting spotted by cameras?”

If you’ve been reading carefully, you’ll know why this reaction doesn’t make sense. Being unrealistic is the selling point of thought experiments, because it allows us to draw out intuitions beyond the reach of our ordinary senses! This is kind of like saying Game of Thrones is unrealistic because ice zombies don’t actually exist.

I think the reason some people respond this way is because they perceive philosophy, rightly or wrongly, as being obsessed with academic minutiae that doesn’t have a practical impact on real life.5 If you already think someone is prone to prattling on about “universal nominalism” or “mereological relations”, then the fantastic scenarios they invent might seem to be an extension of that tendency. But they aren’t, because the intuitions that thought experiments get at are very real and have very concrete uses.

Not Respecting the Experiment’s Rules

“I would heroically rush onto the tracks and untie the one person, so I can redirect the trolley there and nobody has to die!”

There are two kinds of people who give this sort of response. The first kind doesn’t understand how thought experiments work and think they’re a kind of writing prompt, or a free-form “what would you do?” scenario. Since such scenarios (e.g. “if you were shipwrecked on a desert island, what’s your plan to survive?”) are popular in casual conversation, it’s understandable that they might get mixed up with thought experiments. But of course that’s not the point of thought experiments at all, which is why this response is confused. Fortunately, it’s easy enough to clear up this misunderstanding, and now that you know what thought experiments are like, you can easily avoid this mistake in the future.

The second kind is someone who thinks they’re being very clever by finding a third way out of the scenario. Maybe they think the thought experiment is a kind of test and “thinking out of the box” is the right answer.6 At other times, they seem to think their interlocutor is trying to “gotcha” them by forcing them to admit they’d kill someone either way.7 They think thought experiments are a cruel way of forcing them to roleplay having blood on their hands - which is why they’re a lot more prone to responding this way to ethical dilemmas where they have to do something nasty than to low-stakes thought experiments like Mary the color-scientist or the Chinese Room.8 Amusingly, philosophers will often adjust their thought experiments to cover these kinds of loopholes. That can lead to exchanges like the following:

A: “I would untie the one person and save everyone!”

B: “Okay, pretend they’re too far away to reach in time then.”

A: “I would call the train company so they can tell the conductor to use the emergency brakes!”

B: “You can’t. The supervillain who tied them up has sabotaged the emergency brakes.”

A: “Then I would pull out the gun I keep on me at all times and shoot out the trolley’s tires!”

B: “You don’t have a gun.”

If you think of thought experiments as a test or competition to find the best answer, this can seem monstrously unfair. You keep coming up with all these awesome solutions, only for your interlocutor to repeatedly change the scenario to shoot them down. How come they get to change the rules on the spot, and you don’t? This feels like goalpost-shifting, or a blatant attempt to railroad9 you into choosing a shitty option.

But if we see thought experiments as ways of drilling into your intuitions, this makes a lot more sense. The trolley problem is meant to test your intuitions about the value of saving lives versus the value of keeping your hands personally clean (or perhaps your intuitions about whether inaction is keeping your hands clean). The answers you give don’t help to achieve that goal, so the philosopher adjusts the scenario to nudge you towards giving an answer that does. This isn’t bad faith on their part; they’re trying to keep the conversation productive by ensuring that the thought experiment does what it’s meant to do. Engaging with thought experiments seriously means recognizing what intuitions it’s trying to draw out and helping them do so by picking the option that best represents your ethical commitments.

One last note: there are rare cases where this sort of response is warranted, and that’s in cases where the thought experiment itself is malformed. For instance, if a thought experiment asks you to choose whether Hitler or Stalin was the morally righteous person between the two, you might be justified saying that both are wrong. Here, the thought experiment is at fault for not considering the possibility that you might decline to assign righteousness to either. Notice, however, that this response still does a good job of drawing out and communicating your legitimate ethical intuition (i.e. that both are horrible people), sticking to the thought experiment’s original goal. That’s what makes it a productive and good faith response. And you ought to be ready with an answer if the philosopher then says, “okay, but if you had to pick one of them as less morally wrong, who would it be?”

Not Understanding Hypotheticals

“It doesn’t matter, because that wouldn’t happen. I’ll never be in a position to choose like that.”

Sometimes this is just a way of phrasing the “unrealistic” complaint, in which case see my remarks about that. But sometimes this is a genuine failure to understand how hypotheticals work - the “but I did have breakfast” response. I don’t have much to say here, because I don’t know how to explain hypotheticals to someone who doesn’t get them on a deep level. I do think that many people who respond like this are trying to signal a belief in some kind of pragmatism, or more broadly, a worldview where they only care about things that directly impact their life. I don’t think this is a very intellectually fruitful worldview. And it might be rooted, once again, in a misunderstanding of what thought experiments are all about. Thought experiments don’t directly affect people, but the intuitions they’re drilling for usually are part of one’s life, and a better understanding of those intuitions leads directly to a better understanding of yourself and your commitments. So I think that even the most down-to-earth pragmatist ought to take them seriously.

I was originally inspired to write this article by seeing Ari Shtein tell the story of someone smart enough to be admitted to Yale make a truly embarassing gaffe in response to a standard utilitarian thought experiment.

Saul Kripke, Naming and Necessity (2001 ed.), p. 42.

For instance, if you admit that Mary does learn something new but also insist that neurophysiology completely explains human behavior, a philosopher might say you’re an epiphenomenalist - or at least have epiphenomenalist intuitions.

Ibid., p. 84. Funnily enough, Kripke himself has been accused of plagiarizing the ideas in that book - although I personally think it’s a muddled, borderline case and am a little unsettled about whether he’s actually a plagiarist. But Ruth Barcan Marcus probably deserves more credit than she actually got, either way.

I think wrongly. Non-philosophers often underestimate just how much philosophy is immensely useful in real life. I might write a separate article about this.

The prevalence of popular media that depicts heroes actually save everyone by doing this might be why this is a common answer. Of course, thought experiments are very different from Hollywood movies.

This is also why some people clam up and stubbornly refuse to give an answer at all to ethical dilemmas. It’s like they’re afraid of being cancelled for saying the wrong thing.

Imagine responding to the Chinese Room experiment with “of course he knows Chinese, I’d sneak a phone with Duolingo installed into the room so he can learn it and do his job better”. That’s how it sounds when someone says they’d find a way to save everyone in the trolley problem.

Pun intended.

This is how I explain it to scientists who don’t understand how philosophical thought experiments work:

The reason the settings of thought experiments differ from the real world is the same reason lab experiments differ from the real world. Just like you're trying to isolate a variable in a natural system, we're trying to isolate a variable in a belief system.

My big complaint is when thought experiments displace other thinking. My middle-schooler had to engage with the trolley problem to a ridiculous degree without the words “utilitarian”, “deontology”, “commission”, let alone “Kant” being anywhere in the lessons. The unintentional takeaway for the kids was that the *starting* point for ethical/moral analysis is artificial extreme situations, rather than those serving as a later fallback in the discussion.